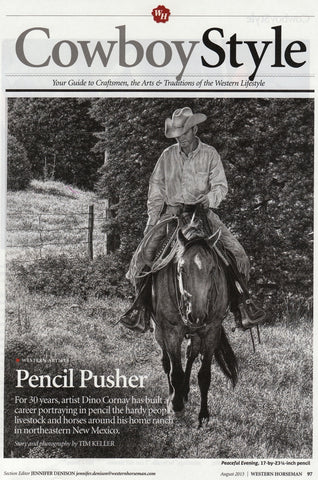

For 30 years, artist Dino Cornay has built a career portraying in pencil the hardy people, livestock and horses around his home ranch in northeastern New Mexico.

Story & Photography by Tim Keller

From the vantage of his studio easel, Western pencil artist Dino Cornay can pause his work to gaze out big picture windows to the craggy grassland on the slopes below Capulin Volcano. His 110-year-old house sits behind the old Doherty Mercantile Co., now a fascinating museum, in downtown Folsom, New Mexico, population 54. Surrounded by family cattle outfits, including his family’s Cornay Ranch, he can count dots of white Charolais cattle grazing in the distance.

Except for four years away at college in Kansas, Cornay has lived his life within four miles of this spot. Although he’s built a career at this easel, the subject matter of his art is always the horses and livestock and people that he’s known since first kicking around the barns.

Except for four years away at college in Kansas, Cornay has lived his life within four miles of this spot. Although he’s built a career at this easel, the subject matter of his art is always the horses and livestock and people that he’s known since first kicking around the barns.

“Growing up on the ranch,” he remembers, “I was steeped in ranching tradition. We rode constantly. I was around cattle all the time. We kids knew how to pull a calf and stack hay. We had to be self-sufficient. We were taught how to work. Not as hard as my dad’s generation, but we worked hard growing up.”

Dino’s dad, Carlos Cornay, 85, still sleeps in the room where he was born, and where his own father was born in 1899. Dino’s great grandfather came from France at age 13 and established the Cornay Ranch in 1865, sharing the land with migrating buffalo herds and peaceful Apaches on one of the first ranches established in the region. The ranch’s V-Diamond brand was registered in 1878.

“When I was a boy,” Dino recalls, “I can never remember not drawing. I drew and drew and drew. I started drawing on the desks at school and got in trouble for it, but eventually the janitors quit wiping my drawings off and left them there.”

At 10, his parents took him to the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth. “I stood before some C.M. Russell paintings. I can still remember seeing the cracks in the oil paints, the paintings were so old, and I stood there awestruck, completely speechless. I wondered, ‘How does somebody do that?’”

Back home at Des Moines School, competition focused on basketball. “But I was a terrible basketball player!” Cornay laughs. Instead, he found a niche in livestock and horse judging at FFA and 4-H competitions. He was so good at judging that it won him a college scholarship at Colby Community College in Kansas. He graduated from Kansas State University with a degree in animal science.

The years of livestock judging helped his artwork, developing expertise in animal anatomy, muscle structure, and movement. “I understand gear, how horses move, how cattle move, how cowboys act, what they do, what they don’t do,” he says. “Horses are noble animals, so beautiful, and I’ve always done well drawing them. A drawing doesn’t even have to have a cowboy in it, as long as it has a horse.”

Someone in Kansas first suggested that he might develop a career in drawing. “My first sale was there at Colby. I made five bucks. That’s when I turned up the volume a bit. But I came home without a plan. I was a country boy with no business sense. My first couple of prints went pretty rough. But by 1984 it kicked in and I started selling some work.”

Nowadays eager collectors scoop up the originals while he sells signed and numbered prints from his studio in editions of 350 to 750. It’s hard to find a business within a hundred miles that doesn’t have at least one Dino Cornay print framed on the wall, and 23 editions have sold out. Much of the business today comes through his website, DinoCornayArt.com, which is also the handiest way to view the breadth of his work.

“I’ve never considered myself a good hand,” he says, “but I can draw horses. I never learned to rope because I didn’t want to risk hurting my hand. I’d rather hold my pencil and my guitar. But I’ve been blessed to be around a lot of good cowboys, guys that live it and breathe it. There’s a lot of them right here, as good as any in the United States.”

He’s as passionate about holding his Fender Telecaster as he is his pencil. “In high school, I got this fever to play the guitar. When I was in the 7th grade, my dad bought me a $19 guitar from Gambles Store in Raton. I started with that. The fever just never went away.

“When I was a little boy, we used to go to the old country dances at Branson, Colorado. I would stand there and watch the band play until I’d get too sleepy and my mom would put a coat down on the floor and I’d fall asleep watching them play. That’s one of the main forms of entertainment we had.” He grew up to be the guitar player on stage, playing in ten bands over the past thirty years. “Playing in bands is getting paid to have fun,” he says. For the past eight years, his band has been Colfax Reunion.

“Whether I’m playing my guitar or drawing, it’s all the same to me. They’re interchangeable. I’m more naturally gifted in drawing and I’ve had to work hard on my guitar playing, but I truly love to play.”

He also loves to supplement his fine art drawing with cartoons and caricatures, looking at the lighter side of life, something he’s enjoyed doing since childhood.

“Art is a constant learning process,” he says. “You never master anything; you’re forever a student. One advantage of art, unlike, say, basketball, is that you can keep doing it, and getting better and growing, all of your life.” He cites Bill Owen, Tim Cox, and pencil artist Robert “Shoofly” Shufelt as influences, but he’s never had any formal training.

“I took one art class in college and got a D. The teacher didn’t like my subject matter. We clashed. My high school art teacher couldn’t help me but she saw my potential and knew enough to point me in a direction and make sure I was drawing or painting every day.

“I’ve studied other people’s work. You’re a fool if you don’t. I’ve been at it a long time and burned up a dump truck load of pencils. With pencil art, you don’t have the luxury of color. You can’t pull their eye in with color, so you’ve got to use contrast to make it three-dimensional.”

He starts with his Nikon camera. “I have 14,000 images in my photo archive. From my photo, I’ll change up the composition, or move a tree or add a cloud, but I’m always true to a cowboy’s or woman’s gear: that is their identity. To not portray that accurately is disrespectful to them. Saddle, chaps, spurs, bridles – you want to be sure you go the extra mile to get their equipment right.”

Seated at his easel, surrounded by a variety of pencils and sharpeners, he says he loves to paint and wants to pursue that more, but the pencils are seductive. “All you need is a piece of paper and a pencil and a sharpener! I’ve seen through the years that people relate to a pencil because everybody starts school using one. When they see what can be done with one – I’ve had little kids go up to a drawing and reach up and touch the glass. It’s touching to see. People say, ‘That’s done with a pencil!’”

Dino’s own daughter, Brooke, 15, is the fifth generation of Cornay to ride horseback across these high volcanic plains of northeastern New Mexico. She’s growing up in the same world Dino has spent his lifetime drawing. “I portray the hardiness of the people,” he says, “like my dad who at 85 can still ride all day. Ranch people are proud. A lot of them grew up on a diet of breathing branding smoke and dust, hot weather, cold weather and snow.”

So he sits in his studio – for up to 300 hours to create a large drawing – and he draws the world he knows. If he runs low on inspiration, all he has to do is look up from his easel and gaze out the big picture windows, pencil in hand.